T-Mobile, Sprint, and AT&T are selling access to their customers’ location data, and that data is ending up in the hands of bounty hunters and others not authorized to possess it, letting them track most phones in the country.

Nervously, I gave a bounty hunter a phone number. He had offered to geolocate a phone for me, using a shady, overlooked service intended not for the cops, but for private individuals and businesses. Armed with just the number and a few hundred dollars, he said he could find the current location of most phones in the United States.

The bounty hunter sent the number to his own contact, who would track the phone. The contact responded with a screenshot of Google Maps, containing a blue circle indicating the phone’s current location, approximate to a few hundred metres.

Queens, New York. More specifically, the screenshot showed a location in a particular neighborhood—just a couple of blocks from where the target was. The hunter had found the phone (the target gave their consent to Motherboard to be tracked via their T-Mobile phone.)

The bounty hunter did this all without deploying a hacking tool or having any previous knowledge of the phone’s whereabouts. Instead, the tracking tool relies on real-time location data sold to bounty hunters that ultimately originated from the telcos themselves, including T-Mobile, AT&T, and Sprint, a Motherboard investigation has found. These surveillance capabilities are sometimes sold through word-of-mouth networks.

Whereas it’s common knowledge that law enforcement agencies can track phones with a warrant to service providers, IMSI catchers, or until recently via other companies that sell location data such as one called Securus, at least one company, called Microbilt, is selling phone geolocation services with little oversight to a spread of different private industries, ranging from car salesmen and property managers to bail bondsmen and bounty hunters, according to sources familiar with the company’s products and company documents obtained by Motherboard. Compounding that already highly questionable business practice, this spying capability is also being resold to others on the black market who are not licensed by the company to use it, including me, seemingly without Microbilt’s knowledge.

Motherboard’s investigation shows just how exposed mobile networks and the data they generate are, leaving them open to surveillance by ordinary citizens, stalkers, and criminals, and comes as media and policy makers are paying more attention than ever to how location and other sensitive data is collected and sold. The investigation also shows that a wide variety of companies can access cell phone location data, and that the information trickles down from cell phone providers to a wide array of smaller players, who don’t necessarily have the correct safeguards in place to protect that data.

“People are reselling to the wrong people,” the bail industry source who flagged the company to Motherboard said. Motherboard granted the source and others in this story anonymity to talk more candidly about a controversial surveillance capability.

Got a tip? You can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

Your mobile phone is constantly communicating with nearby cell phone towers, so your telecom provider knows where to route calls and texts. From this, telecom companies also work out the phone’s approximate location based on its proximity to those towers.

Although many users may be unaware of the practice, telecom companies in the United States sell access to their customers’ location data to other companies, called location aggregators, who then sell it to specific clients and industries. Last year, one location aggregator called LocationSmart faced harsh criticism for selling data that ultimately ended up in the hands of Securus, a company which provided phone tracking to low level enforcement without requiring a warrant. LocationSmart also exposed the very data it was selling through a buggy website panel, meaning anyone could geolocate nearly any phone in the United States at a click of a mouse.

There’s a complex supply chain that shares some of American cell phone users’ most sensitive data, with the telcos potentially being unaware of how the data is being used by the eventual end user, or even whose hands it lands in. Financial companies use phone location data to detect fraud; roadside assistance firms use it to locate stuck customers. But AT&T, for example, told Motherboard the use of its customers’ data by bounty hunters goes explicitly against the company’s policies, raising questions about how AT&T allowed the sale for this purpose in the first place.

“The allegation here would violate our contract and Privacy Policy,” an AT&T spokesperson told Motherboard in an email.

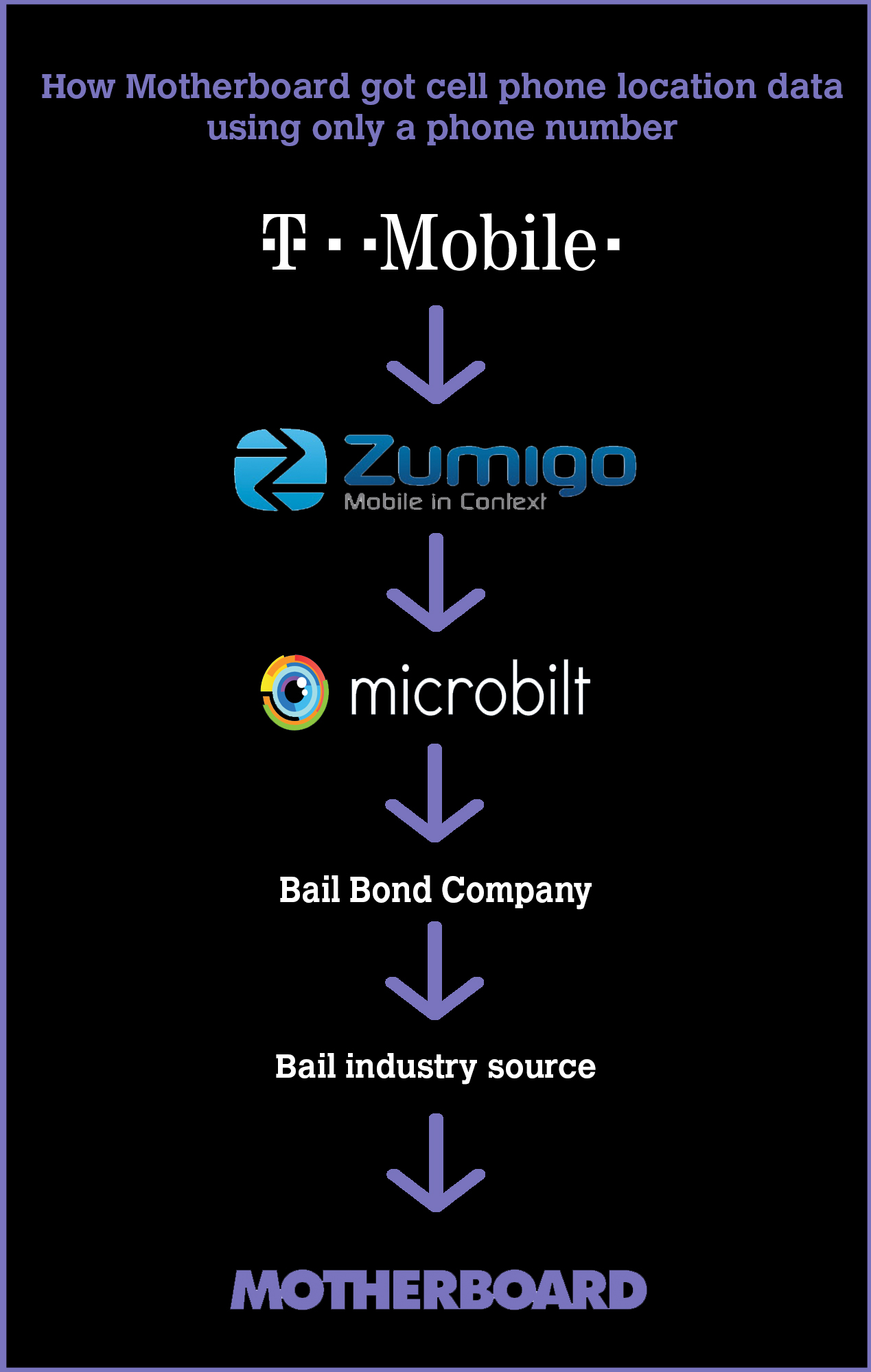

In the case of the phone we tracked, six different entities had potential access to the phone’s data. T-Mobile shares location data with an aggregator called Zumigo, which shares information with Microbilt. Microbilt shared that data with a customer using its mobile phone tracking product. The bounty hunter then shared this information with a bail industry source, who shared it with Motherboard.

The CTIA, a telecom industry trade group of which AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile are members, has official guidelines for the use of so-called “location-based services” that “rely on two fundamental principles: user notice and consent,” the group wrote in those guidelines. Telecom companies and data aggregators that Motherboard spoke to said that they require their clients to get consent from the people they want to track, but it’s clear that this is not always happening.

A second source who has tracked the geolocation industry told Motherboard, while talking about the industry generally, “If there is money to be made they will keep selling the data.”

“Those third-level companies sell their services. That is where you see the issues with going to shady folks [and] for shady reasons,” the source added.

Frederike Kaltheuner, data exploitation programme lead at campaign group Privacy International, told Motherboard in a phone call that “it’s part of a bigger problem; the US has a completely unregulated data ecosystem.”

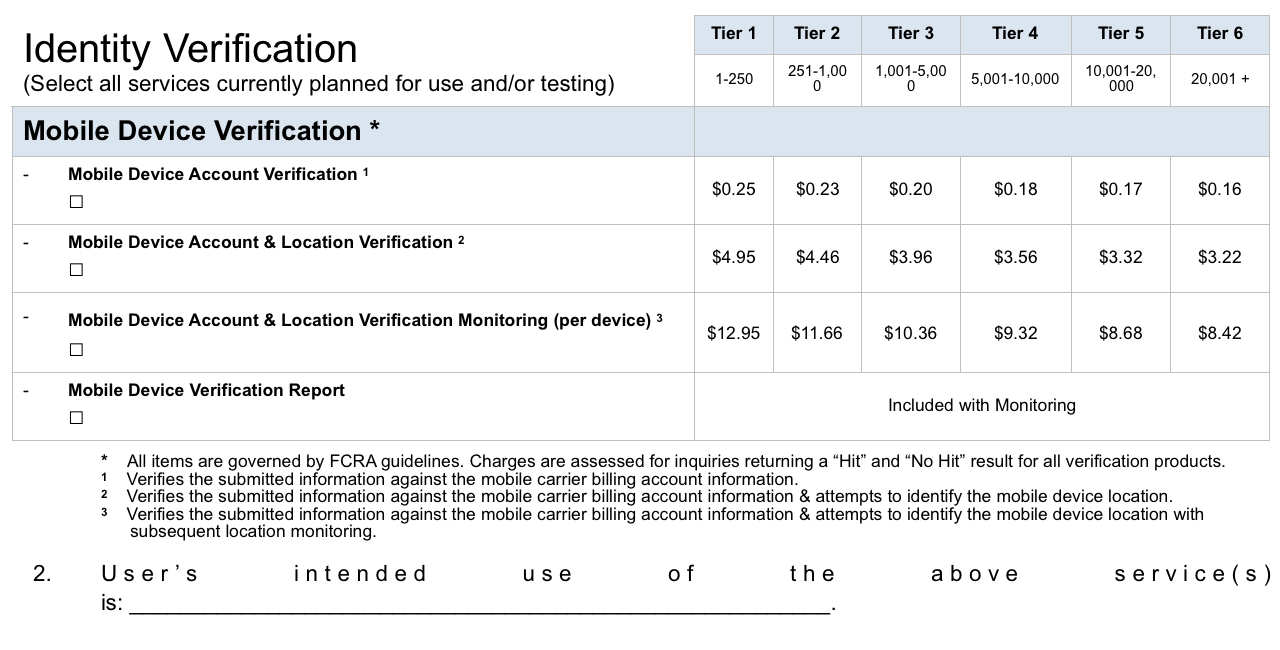

Microbilt buys access to location data from an aggregator called Zumigo and then sells it to a dizzying number of sectors, including landlords to scope out potential renters; motor vehicle salesmen, and others who are conducting credit checks. Armed with just a phone number, Microbilt’s “Mobile Device Verify” product can return a target’s full name and address, geolocate a phone in an individual instance, or operate as a continuous tracking service.

“You can set up monitoring with control over the weeks, days and even hours that location on a device is checked as well as the start and end dates of monitoring,” a company brochure Motherboard found online reads.

Posing as a potential customer, Motherboard explicitly asked a Microbilt customer support staffer whether the company offered phone geolocation for bail bondsmen. Shortly after, another staffer emailed with a price list—locating a phone can cost as little as $4.95 each if searching for a low number of devices. That price gets even cheaper as the customer buys the capability to track more phones. Getting real-time updates on a phone’s location can cost around $12.95.

“Dirt cheap when you think about the data you can get,” the source familiar with the industry added.

It’s bad enough that access to highly sensitive phone geolocation data is already being sold to a wide range of industries and businesses. But there is also an underground market that Motherboard used to geolocate a phone—one where Microbilt customers resell their access at a profit, and with minimal oversight.

“Blade Runner, the iconic sci-fi movie, is set in 2019. And here we are: there's an unregulated black market where bounty-hunters can buy information about where we are, in real time, over time, and come after us. You don't need to be a replicant to be scared of the consequences,” Thomas Rid, professor of strategic studies at Johns Hopkins University, told Motherboard in an online chat.

The bail industry source said his middleman used Microbilt to find the phone. This middleman charged $300, a sizeable markup on the usual Microbilt price. The Google Maps screenshot provided to Motherboard of the target phone’s location also included its approximate longitude and latitude coordinates, and a range of how accurate the phone geolocation is: 0.3 miles, or just under 500 metres. It may not necessarily be enough to geolocate someone to a specific building in a populated area, but it can certainly pinpoint a particular borough, city, or neighborhood.

In other cases of phone geolocation it is typically done with the consent of the target, perhaps by sending a text message the user has to deliberately reply to, signalling they accept their location being tracked. This may be done in the earlier roadside assistance example or when a company monitors its fleet of trucks. But when Motherboard tested the geolocation service, the target phone received no warning it was being tracked.

The bail source who originally alerted Microbilt to Motherboard said that bounty hunters have used phone geolocation services for non-work purposes, such as tracking their girlfriends. Motherboard was unable to identify a specific instance of this happening, but domestic stalkers have repeatedly used technology, such as mobile phone malware, to track spouses.

As Motherboard was reporting this story, Microbilt removed documents related to its mobile phone location product from its website.

A Microbilt spokesperson told Motherboard in a statement that the company requires anyone using its mobile device verification services for fraud prevention must first obtain consent of the consumer. Microbilt also confirmed it found an instance of abuse on its platform—our phone ping.

“The request came through a licensed state agency that writes in approximately $100 million in bonds per year and passed all up front credentialing under the pretense that location was being verified to mitigate financial exposure related to a bond loan being considered for the submitted consumer,” Microbilt said in an emailed statement. In this case, “licensed state agency” is referring to a private bail bond company, Motherboard confirmed.

“As a result, MicroBilt was unaware that its terms of use were being violated by the rogue individual that submitted the request under false pretenses, does not approve of such use cases, and has a clear policy that such violations will result in loss of access to all MicroBilt services and termination of the requesting party’s end-user agreement,” Microbilt added. “Upon investigating the alleged abuse and learning of the violation of our contract, we terminated the customer’s access to our products and they will not be eligible for reinstatement based on this violation.”

Zumigo confirmed it was the company that provided the phone location to Microbilt and defended its practices. In a statement, Zumigo did not seem to take issue with the practice of providing data that ultimately ended up with licensed bounty hunters, but wrote, “illegal access to data is an unfortunate occurrence across virtually every industry that deals in consumer or employee data, and it is impossible to detect a fraudster, or rogue customer, who requests location data of his or her own mobile devices when the required consent is provided. However, Zumigo takes steps to protect privacy by providing a measure of distance (approx. 0.5-1.0 mile) from an actual address.” Zumigo told Motherboard it has cut Microbilt’s data access.

"People are reselling to the wrong people."

In Motherboard’s case, the successfully geolocated phone was on T-Mobile.

“We take the privacy and security of our customers’ information very seriously and will not tolerate any misuse of our customers’ data,” A T-Mobile spokesperson told Motherboard in an emailed statement. “While T-Mobile does not have a direct relationship with Microbilt, our vendor Zumigo was working with them and has confirmed with us that they have already shut down all transmission of T-Mobile data. T-Mobile has also blocked access to device location data for any request submitted by Zumigo on behalf of Microbilt as an additional precaution.”

Microbilt’s product documentation suggests the phone location service works on all mobile networks, however the middleman was unable or unwilling to conduct a search for a Verizon device. Verizon did not respond to a request for comment.

AT&T told Motherboard it has cut access to Microbilt as the company investigates.

“We only permit the sharing of location when a customer gives permission for cases like fraud prevention or emergency roadside assistance, or when required by law,” the AT&T spokesperson said.

Sprint told Motherboard in a statement that “protecting our customers’ privacy and security is a top priority, and we are transparent about that in our Privacy Policy [...] Sprint does not have a direct relationship with MicroBilt. If we determine that any of our customers do and have violated the terms of our contract, we will take appropriate action based on those findings.” Sprint would not clarify the contours of its relationship with Microbilt.

These statements sound very familiar. When The New York Times and Senator Ron Wyden published details of Securus last year, the firm that was offering geolocation to low level law enforcement without a warrant, the telcos said they were taking extra measures to make sure their customers’ data would not be abused again. Verizon announced it was going to limit data access to companies not using it for legitimate purposes. T-Mobile, Sprint, and AT&T followed suit shortly after with similar promises.

After Wyden’s pressure, T-Mobile’s CEO John Legere tweeted in June last year “I’ve personally evaluated this issue & have pledged that @tmobile will not sell customer location data to shady middlemen.”

"It appears these promises were little more than worthless spam in their customers’ inboxes."

Months after the telcos said they were going to combat this problem, in the face of an arguably even worse case of abuse and data trading, they are saying much the same thing. Last year, Motherboard reported on a company that previously offered phone geolocation to bounty hunters; here Microbilt is operating even after a wave of outrage from policy makers. In its statement to Motherboard on Monday, T-Mobile said it has nearly finished the process of terminating its agreements with location aggregators.

“It would be bad if this was the first time we learned about it. It’s not. Every major wireless carrier pledged to end this kind of data sharing after I exposed this practice last year. Now it appears these promises were little more than worthless spam in their customers’ inboxes,” Wyden told Motherboard in a statement. Wyden is proposing legislation to safeguard personal data.

Due to the ongoing government shutdown, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was unable to provide a statement.

“Wireless carriers’ continued sale of location data is a nightmare for national security and the personal safety of anyone with a phone,” Wyden added. “When stalkers, spies, and predators know when a woman is alone, or when a home is empty, or where a White House official stops after work, the possibilities for abuse are endless.”

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.